Research

Infant Feeding Choices and the Role of Policy Design

Although women have been graduating from college at higher rates than men for decades, the gender pay gap persists – especially after the birth of a first child. One factor that’s often overlooked: breastfeeding. In her research project, Alison Doxey will explore how much breastfeeding contributes to the so-called “child penalty” and whether targeted policies could help support both infant health and mothers’ careers.

For nearly 30 years, more women than men have graduated from college each year in the United States.1 However, there is a persistent gender pay gap that tends to grow over the course of people’s careers; a phenomenon observed in many Western countries. In high-income countries like the U.S., the gender pay gap is driven by women decreasing their time at work when they have their first child – either quitting their jobs to take care of the baby full-time or decreasing their work hours.

Why do many mothers step back from their careers after having a child, but fathers don’t? Until recently, most research in economics has focused on work-related factors that influence this “child penalty” for mothers. For example, men are more likely to choose jobs that reward long, inflexible hours, while women choose jobs with more flexibility and lower pay. However, factors outside of work might be important too, even though they’re harder to study. Raising a child requires a lot of investments at home – not only childcare but also preparing meals and cleaning the house – and there may be gender differences in these investments as well.

It’s tempting to attribute these gender differences in household work to entrenched gender norms and simply encourage opposite-sex couples to share the load equally. Indeed, most tasks at home can be done by either domestic partner. Anyone can sweep a floor or read a child a bedtime story. But there is one critical task that cannot be shared equally between partners (or outsourced to another caregiver), and that is breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding is both time-intensive and time-sensitive; during the first six months of life, an infant needs milk every 2 to 3 hours during the day and a single feeding can range from 15 to 30 minutes or more. Unless a mother has access to a breast pump or breastfeeding alternative, she can only spend 1.5 to 2.5 hours away from her baby at a time, making it very difficult to leave home for work. Even if a woman earned just as much as her partner before childbirth, her decision to breastfeed could naturally lead her to take charge of household tasks – and pull back on market work – since breastfeeding keeps her at home more often anyway. And after the child stops breastfeeding, the mother may continue to be the parent “on call” at home because she has learned more about the child’s schedule, needs, and preferences.2

This process could change substantially once high-quality alternatives to breastfeeding are introduced. For example, access to a breast pump allows a woman to spend longer stretches of time away from her baby. Additionally, using infant formula allows women to avoid the frequent interruptions to the workday that are required when using a breast pump.

Higher breastfeeding rates, higher child penalties?

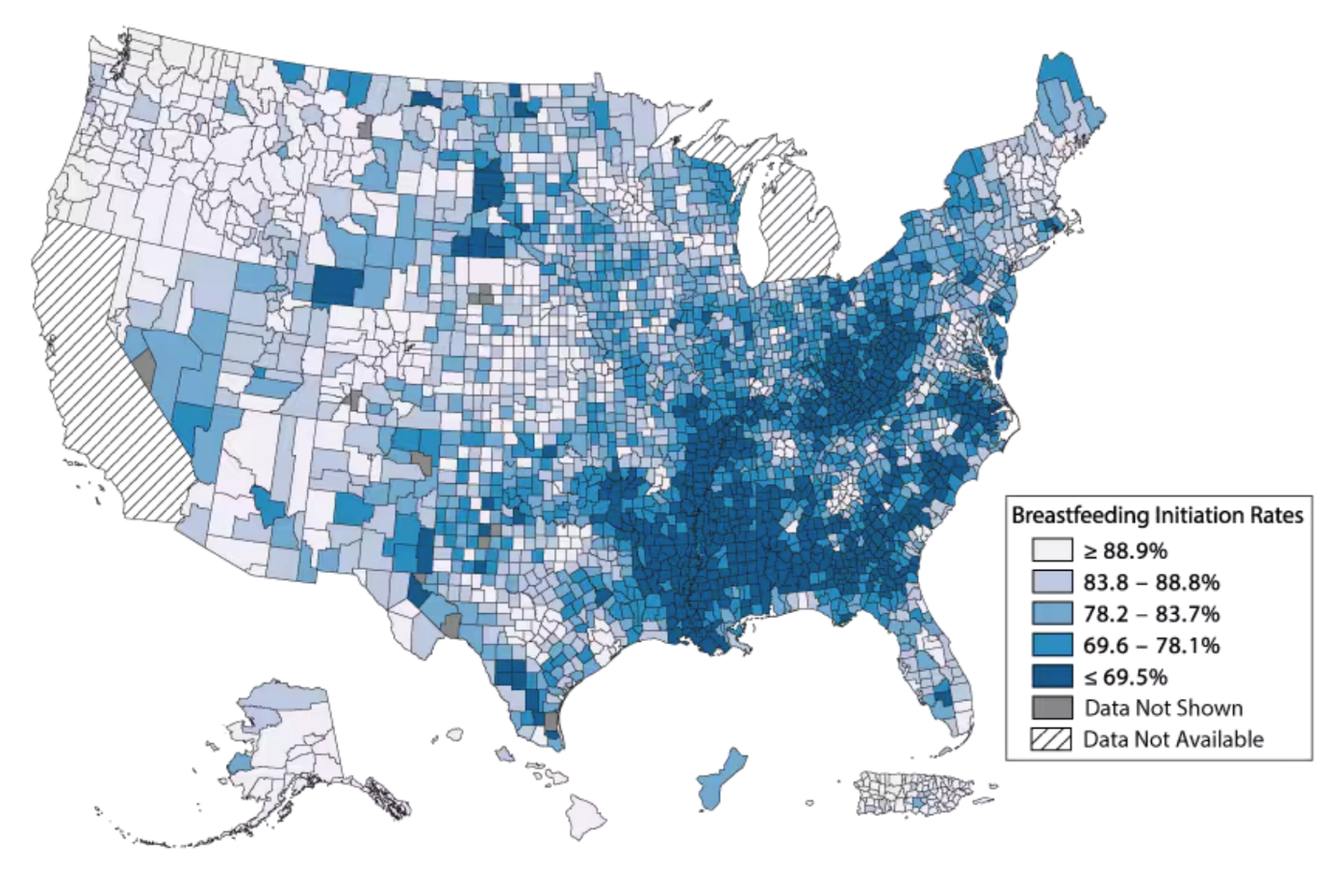

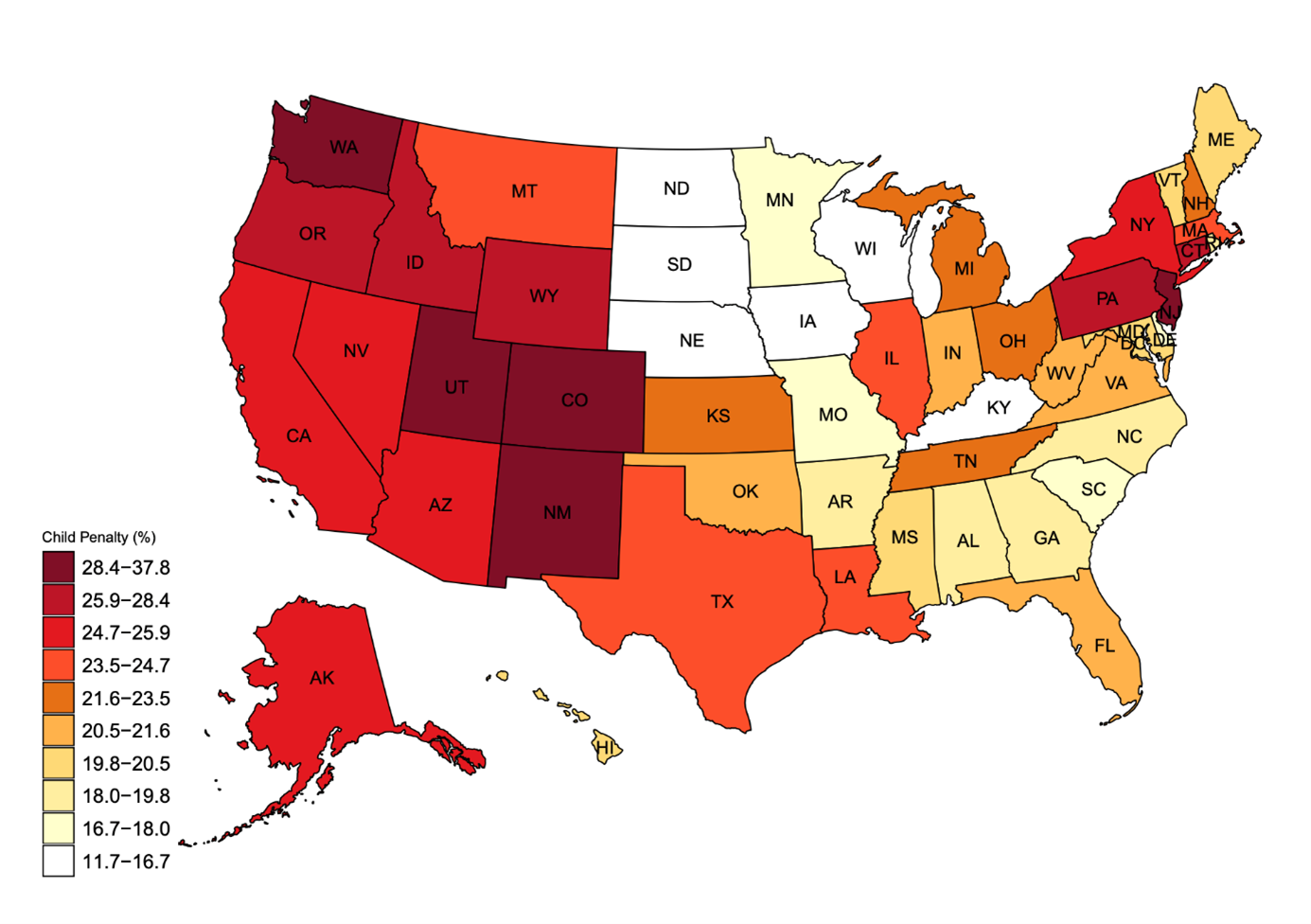

Indeed, there appears to be a strong correlation between breastfeeding rates and new mothers’ reductions in employment in the United States (see figure). For example, the Pacific Northwest has both high breastfeeding rates (at top) and high child penalties in employment (at bottom). This is striking because states like Oregon, Washington, and Colorado are much more politically liberal than Utah or Idaho, yet both sets of places see similarly large reductions in women’s employment after having a child. These are, however, just associations. To date, there is very little evidence on the causal effect of breastfeeding on mothers’ careers. My research seeks to fill that gap.

Understanding the link between breastfeeding and maternal employment is important from both a policy and individual perspective. The WHO recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months, yet many countries around the world do not offer such long maternity leaves. Mothers thus face a trade-off between breastfeeding or going back to work. In this project, I aim to shed light on this trade-off by investigating the long-run effect of a change in the relative cost of breastfeeding on women’s labor force participation.

I plan to study policies that have significantly changed the price of infant formula to see whether making formula more accessible has led women to work more, spend less time out of the labor force, and earn more. The results of this project will have clear implications for parental leave policies and public policy around subsidizing alternatives to breastfeeding. My goal is to better understand how breastfeeding choices and incentives relate to gender inequality in the labor market.

- Hurst, Kiley. “U.S. Women Are Outpacing Men in College Completion, Including in Every Major Racial and Ethnic Group.” Pew Research Center, November 18, 2024.

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/11/18/us-women-are-outpacing-men-in-college-completion-including-in-every-major-racial-and-ethnic-group/. - Goldin, Claudia. Career and Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity. Princeton University Press, 2021.